Christmas Traditions for London’s Rich and Poor

Traditional Christmas celebrations for both the landed gentry and their servants were reintroduced in the Georgian era, following a ban imposed by Oliver Cromwell in 1644 that lasted 70 years. Whether residing in London or the country many of the seasonal activities and customs would have been the same, but the scale and lavishness of Christmas celebrations was very different according to one’s status and wealth.

A month of Christmas fun

In Georgian times, for the wealthy residents living in the palatial townhouses across Belgravia, Mayfair, Kensington and Hyde Park, Christmas lasted an entire month. There would be extravagant balls, parties and family gatherings attended by the great and the good. Festivities started on St Nicholas Day, December 6th with family and friends traditionally exchanging presents to mark the first day of the Christmas season, and ended with dancing and celebrations on Twelfth Night on January 6th. This continued until the 1870’s when Queen Victoria outlawed Twelfth Night celebrations deeming it too indulgent.

It was near the end of the Georgian period with the rise of the Industrial Revolution, the decline of rural living and the creeping urbanisation of London, when this extended Christmas season disappeared to allow employees to continue working throughout the festive period.

For the servants and staff, festivities aside, it was always a busy work period attending to and waiting on their employers to ensure the household and the stables ran like clockwork. From the 18th century, the Mews were, of course, used for equine purposes where the horses, carriages and coaches were kept. Under the supervision of the coachman, the stable-hands and grooms worked long days and lived in humble conditions above the stables.

Throughout the festive season, the Mews streets would have been a hive of activity with the constant rattle of wheels and hooves over cobbles, the scraping of shovels, straw strewn around and men shouting instructions as they went about their daily duties.

Christmas Boxes

While the aristocracy and elite celebrated Christmas Day, their servants and stable-hands, grooms and livery staff would look forward to celebrating the day after Christmas, known as St Stephen’s Day. On the 26th December, they would be given this day off to spend with their own families. Staff would receive Christmas boxes containing gifts, clothing and food from their employers. It is from this tradition that ‘Boxing Day’ derives its name and the practice continued through the Victorian period and beyond.

Christmas Stockings

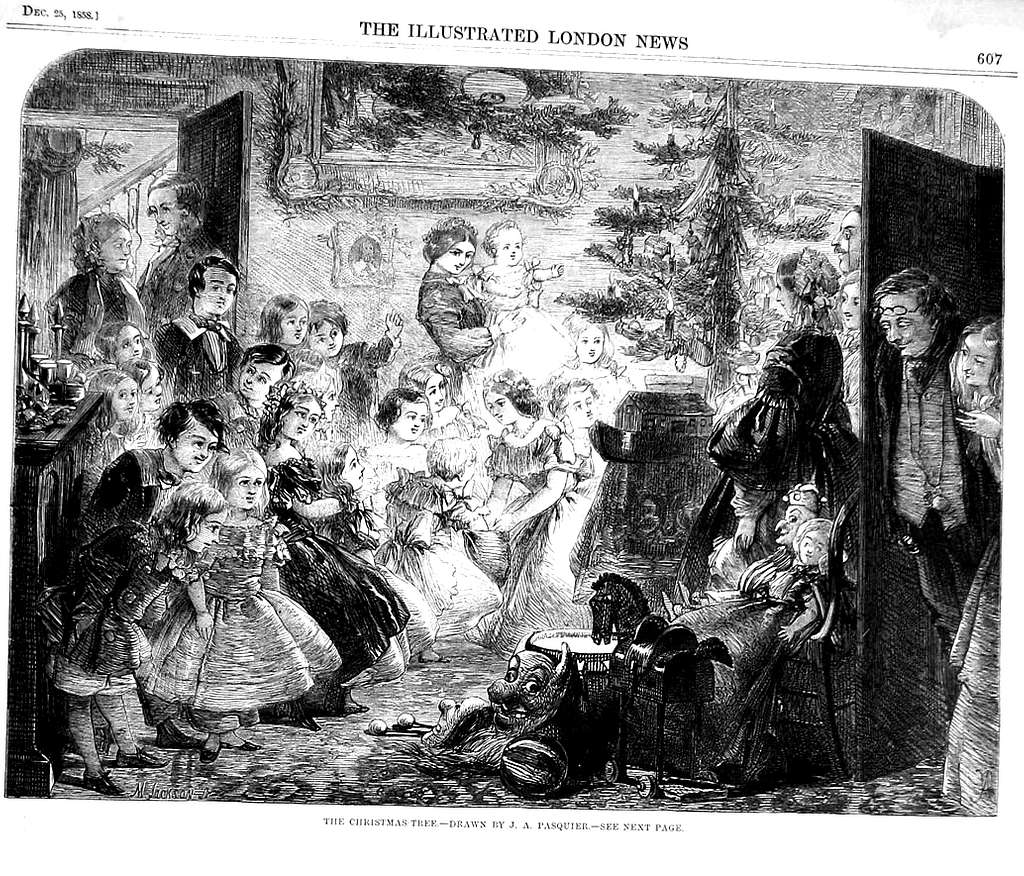

Victorian times saw the children of the poor receive stockings filled with fruit and nuts, a tradition we still have today. Once again, the Industrial Revolution brought about change and introduced mass production, factories were able to produce toys more rapidly and much less expensively, so they became more accessible to all. Those who had practical skills and access to tools such as Mews staff, might carve or make wooden toys, dolls and carts to give their children and younger siblings at Christmas.

Christmas Games

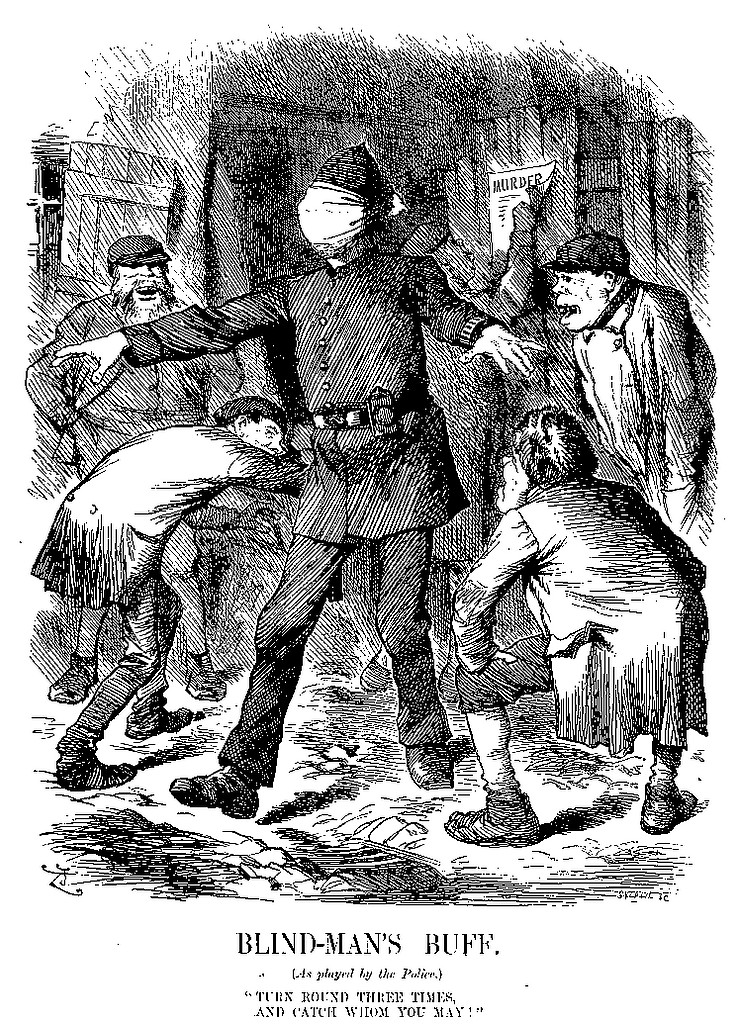

Servants and Mews stable-hands would enjoy singing carols and playing games at Christmas throughout Georgian and Victorian times. They would often play cards, charades and games – Blind-Man’s Buff’ and ‘Hunt The Slipper’. Another popular 18th century game that reflected the Mews’ equine purpose was ‘Shoe The Wild Mare’, which involved a player (the ‘farrier’) sitting astride a wooden beam (the ‘mare’) suspended from the roof and hammering the underside of the beam (as if shoeing the mare) until he fell off!

Festive Feasts and Fare

Food has always played a very important part during Christmas, through the ages. At the start of the Georgian era, various roasts and fowl were common at the Christmas table. Towards the end of this period, turkey started to become the most popular meat, although venison was popular with the gentry. Other typical Christmas foods during this period were cheese, soups, minced pies, and frumenty – a dish which contained grains, almonds, currants, sugar and was often served with meat. Unlike today’s mince pies, Georgian mince pies were originally made from made from ox tongue and other meat using fruit and spices. Everybody would tuck into jellies and Christmas Pudding was also known as ‘plum pottage’ and contained dried prunes or raisins. By Victorian times the dish had evolved into ‘plum pudding’.

The Servant and the Pea

The ‘Twelfth Cake’, similar to today’s Christmas Cake, was the centrepiece of the Twelfth Night party held on January 6th. The cake contained both a dried bean and a dried pea. A slice was given to all members of the household, including servants. The man whose slice contained the bean was King for the night and the woman who received the pea was elected Queen. For the rest of the evening, they ruled. Even if they were servants, their temporary position was recognised by all, including their masters.

By the Regency period, Twelfth Cake became more elaborate with added icing, trimmings and figurines. It continued to be the centrepiece of the party, although the bean and pea were usually omitted and presumably the servants no longer traded places with their masters.

Wassail Toast

The word itself comes from Old Norse and means ‘good health’ and wassailing is an old English Yuletide celebration.

In well-to-do households, large ‘wassail’ bowls were raised to drink to the health of everyone present – like a modern-day toast – then the bowl would be passed around the room, and everyone would take a drink. In the Mews and main house’s servants’ quarters, staff would toast to ‘good health in the New Year’ raising a wassail cup containing spicy ale made with sugar, cinnamon, ginger, and nutmeg.

In Victorian times, a spicy wassail brew called ‘Smoking Bishop’ – a type of mulled wine or punch became especially popular at Christmas time, and is mentioned in Charles Dickens’ 1843 story ‘A Christmas Carol’.

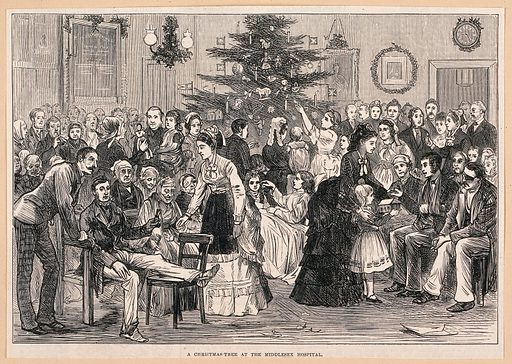

Decorations

During the Georgian period, Christmas decorations, including holly and evergreens, were brought into the home on Christmas Eve as it was believed to be unlucky to bring greenery indoors before. Servants would decorate their homes with seasonal evergreen garlands and sprigs of foliage such as holly, ivy, herbs, and mistletoe. By the late 18th Century, kissing boughs and balls were popular. These were often decorated with spices, apples, oranges, candles or ribbons. Once Twelfth Night was over, all the decorations were taken down and the greenery was burned to avoid bad luck – a tradition that continues today.

The Christmas tree had not been adopted by the British people in the Georgian times, however, it is believed that a Christmas tree was brought to Court in 1800 by Queen Charlotte, wife of George III.

Yule Logs and Fires

A fire was the centrepiece of a family Christmas. The Yule Log was chosen on Christmas Eve and wrapped in hazel twigs before being burned in the fireplace for as long as possible through the Christmas season. The tradition was to keep back a piece of the Yule log to light next Christmas.

On Christmas Day everyone would go to church, although religion was deeply divided between Protestants, Catholics and some Jacobite supporters in Georgian times, before returning for a celebratory Christmas dinner.

‘It’s behind you…’ Londoner’s love of Pantomime

Not directions to the Mews, but one of many stage phrases we all know from trips to the panto. The classic British panto owes much to the Victorians who brought their stars from the music hall onto the theatre stage as the harlequinade era disappeared – a casualty of respectability.

For the Victorian middle classes, watching policemen being beaten was no longer a form of entertainment. But at the same time, music hall artists introduced the plots, dilemmas and conversations of working-class culture. With this came a more raucous, bawdy and suggestive edge, that attracted those from the same social background, who could enjoy the familiar jigs and dances, the skits and join in with their familiar favourite songs.

Even today in modern times, we still get together to celebrate and make merry enjoying many of the elements that were part of Christmas traditions long ago. The magic of Christmas is that it’s a time when ritual and nostalgia bring comfort and joy to us all, whilst giving us an opportunity to start new traditions and make more seasonal memories in the Mews.